February is recognized as Black History Month in the United States. Traditionally, its focus has been to celebrate the contributions of African Americans in the U.S.

Carter G. Woodson pioneered the celebration that started as out as a week in February in 1926, to its current month-long celebration. As we approach the opening of the Friendship store in Bryant neighborhood, it is important that we honor the legacy of African Americans in the co-op community.

The book Collective Courage by Jessica Gordon Nembhard documents the importance of cooperative economics in the African American community. In that book, Dr. Nembhard covers decades of experiences that African Americans have had with cooperative economics.

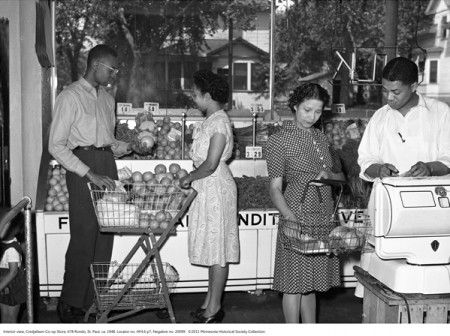

Customers at Minnesota’s Credjafawn Co-op in the predominantly African-American Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul, circa 1950.

Dr. Nembhard’s book is a continuation of the 1907 survey of African American cooperative efforts written by W.E.B. Du Bois. Du Bois discussed how African Americans used racial solidarity and economic cooperation in the face of discrimination and marginalization.

According to Dr. Nembhard, Du Bois differentiated cooperative economics from Black capitalism or buying Black. Du Bois focused on a “Black group economy” to insulate Blacks from continued segregation and marginalization.

To achieve that goal, Du Bois organized the Negro Cooperative Guild in 1918 with the idea of advancing cooperation among Black people. In attendance at the two-day conference were 12 men from seven states.

Du Bois is most widely known for his statement regarding race relations in the U.S. In his book, The Souls of Black Folk, he famously noted that “the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line.”

Du Bois is noted for accurately describing the problems of race in America. Yet, his work to solve the problem of the color line is often ignored. Du Bois promoted economic cooperation as the solution to the issues of the “color line.”

Du Bois said that “we unwittingly stand at the crossroads—should we go the way of capitalism and try to become individually rich as capitalists, or should we go the way of cooperatives and economic cooperation where we and our whole community could be rich together?”

In this instance, Du Bois believed that economic cooperation could provide more than providers of goods or services, but also a philosophy or blueprint by which communities could be built or rebuilt.

The guild’s mission was to encourage the study of consumer cooperatives and their methods, support the development of cooperative stores, and form a technical assistance committee.

As a result of the meeting of the guild, in 1919, the Memphis group incorporated as the Citizens’ Co-operative Stores to operate cooperative meat markets. The venture was very popular. The cooperative sold double the amount of the original shares they offered, and members could buy shares in installments.

Within a few months, five stores were in operation in Memphis, serving about 75,000 people. The members of the local guilds associated with each store met monthly to study cooperatives and discuss issues. The cooperative planned to own its own buildings and a cooperative warehouse.

The use of cooperative economics to address racial discrimination in the market place and provide a pathway to rebuild communities is an important lesson that has relevance today.

Since the 1800s, Minnesota food co-operatives have been at the center of issues that juxtapose the pursuit of justice issues against fair market opportunity. This started with the Finnish who arrived in Northern Minnesota, Scandinavian farmers who were taking bottom-barrel prices from railroad barons, extended into the 1950s when Black Minnesotans organized the Credjafawn Co-op to benefit their community in St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood. The co-ops were at the center of these issues in the 1970s, too, wherein the “Co-op Wars” erupted over social justice issues versus profitability.

We know that these are false dichotomies. A single choice among fairness, equity, or justice is not an option. Justice in the marketplace is not an option. Economic exploitation is not a part of the model of sustainability, and neither is economic isolation. The opportunity to share the co-operative model is at hand.

During the Co-op Wars of the ’70s, the clash between the Maoist “Co-op Organization” and the Bryant/Central Food Co-op was not just about food. The clash was about the false dichotomies: Serving poor people OR serving great food. Dismantling the notion that “cheap” food is sustainable is hard.

However, we now know that cheap food is built on cheap labor. When people are not paid fairly, we perpetuate the same system of inequality that we are trying to end. Today’s food co-ops must accomplish both: Make a commitment to end poverty by supporting economic models that are fair, just, and healthy and deliver healthful food to its owners.

The Seward Co-op’s Friendship store in a Bryant neighborhood will be an opportunity to become a part of the fabric of the community that honors this legacy by bridging the gap between the promise of cooperatives of the past and an economically just future.

Would you like to discuss these ideas further? Join LaDonna for the Seward Co-op Book Club this month —Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice

Sure, about a month ago it was Christmas Island and a month forward in time, it will be Mardi Gras or St. Patrick’s Day Island.