Search Results

My Account

Login

Guide to Winter Squash

Not sure what to do with all the gorgeous winter squash in Produce? National Co-op Grocers has compiled descriptions of common varieties, as well as some handy tips for selecting the right squash for you and plenty of delicious squash recipes you’ll love.

General selection tips

Winter squash are harvested late summer through fall, then “cured” or “hardened off” in open air to toughen their exterior. This process ensures the squash will keep for months without refrigeration. Squash that has been hurried through this step and improperly cured will appear shiny and may be tender enough to be pierced by your fingernail. When selecting any variety of winter squash, the stem is the best indication of ripeness. Stems should be tan, dry, and on some varieties, look fibrous and frayed, or corky. Fresh green stems and those leaking sap signal that the squash was harvested before it was ready. Ripe squash should have vivid, saturated (deep) color and a matte, rather than glossy, finish.

Acorn

This forest green, deeply ribbed squash resembles its namesake, the acorn. It has yellow-orange flesh and a tender-firm texture that holds up when cooked. Acorn’s mild flavor is versatile, making it a traditional choice for stuffing and baking. The hard rind is not good for eating, but helps the squash hold its shape when baked.

Selection: Acorn squash should be uniformly green and matte—streaks/spots of orange are fine, but too much orange indicates over ripeness and the squash will be dry and stringy.

Best uses: baking, stuffing, mashing.

Other varieties: all-white “Cream of the Crop,” and all-yellow “Golden Acorn.”

Blue Hubbard

Good for feeding a crowd, these huge, bumpy textured squash look a bit like a giant gray lemon, tapered at both ends and round in the middle. A common heirloom variety, Blue Hubbard has an unusual, brittle blue-gray outer shell, a green rind, and bright orange flesh. Unlike many other winter squashes, they are only mildly sweet, but have a buttery, nutty flavor and a flaky, dry texture similar to a baked potato.

Selection: Choose a squash based on size—1 pound equals approximately 2 cups of chopped squash (tip: if you don’t have use for the entire squash, some produce departments will chop these into smaller pieces for you).

Best Uses: baked or mashed, topped with butter, sea salt, and freshly ground black pepper.

Other varieties: Golden or Green Hubbard, Baby Blue Hubbard.

Butternut

These squash are named for their peanut-like shape and smooth, beige coloring. Butternut is a good choice for recipes calling for a large amount of squash because they are dense—the seed cavity is in the small bulb opposite the stem end, so the large stem is solid squash. Their vivid orange flesh is sweet and slightly nutty with a smooth texture that falls apart as it cooks. Although the rind is edible, butternut is usually peeled before use.

Selection: Choose the amount of squash needed by weight. One pound of butternut equals approximately 2 cups of peeled, chopped squash.

Best uses: soups, purees, pies, recipes where smooth texture and sweetness will be highlighted.

Delicata

This oblong squash is butter yellow in color with green mottled striping in shallow ridges. Delicata has a thin, edible skin that is easy to work with but makes it a poor squash for long-term storage; this is why you’ll only find them in the fall. The rich, sweet yellow flesh is flavorful and tastes like chestnuts, corn, and sweet potatoes.

Selection: Because they are more susceptible to breakdown than other winter squash, take care to select squash without scratches or blemishes, or they may spoil quickly.

Best Uses: Delicata’s walls are thin, making it a quick-cooking squash. It can be sliced in 1/4-inch rings and sautéed until soft and caramelized (remove seeds first), halved and baked in 30 minutes, or broiled with olive oil or butter until caramelized.

Other varieties: Sugar Loaf and Honey Boat are varieties of Delicata that have been crossed with Butternut. They are often extremely sweet with notes of caramel, hazelnut, and brown sugar (They’re delicious and fleeting, so we recommend buying them when you find them!).

Heart of Gold/Festival/Carnival

These colorful, festive varieties of squash are all hybrids resulting from a cross between Sweet Dumpling and Acorn, and are somewhere between the two in size. Yellow or cream with green and orange mottling, these three can be difficult to tell apart, but for culinary purposes, they are essentially interchangeable. With a sweet nutty flavor like Dumpling, and a tender-firm texture like Acorn, they are the best of both parent varieties.

Selection: Choose brightly colored squash that are heavy for their size.

Best uses: baking, stuffing, broiling with brown sugar.

Kabocha (Green or Red)

Green KabochaKabocha can be dark green with mottled blue-gray striping, or a deep red-orange color that resembles Red Kuri. You can tell the difference between red Kabocha and Red Kuri by their shape: Kabocha is round but flattened at stem end, instead of pointed. The flesh is smooth, dense, and intensely yellow. They are similar in sweetness and texture to a sweet potato.

Selection: Choose heavy, blemish free squash. They may have a golden or creamy patch where they rested on the ground.

Best Uses: curries, soups, stir-fry, salads.

Other varieties: Buttercup, Turban, Turk’s Turban.

Pie Pumpkin

Pie pumpkins differ from larger carving pumpkins in that they have been bred for sweetness and not for size. They are uniformly orange and round with an inedible rind, and are sold alongside other varieties of winter squash (unlike carving pumpkins which are usually displayed separately from winter squash). These squash are mildly sweet and have a rich pumpkin flavor that is perfect for pies and baked goods. They make a beautiful centerpiece when hollowed out and filled with pumpkin soup.

Selection: Choose a pie pumpkin that has no hint of green and still has a stem attached; older pumpkins may lose their stems.

Best uses: pies, custards, baked goods, curries and stews.

Red Kuri

These vivid orange, beta carotene-saturated squash are shaped like an onion, or teardrop. They have a delicious chestnut-like flavor, and are mildly sweet with a dense texture that holds shape when steamed or cubed, but smooth and velvety when pureed, making them quite versatile.

Selection: Select a smooth, uniformly colored squash with no hint of green.

Best Uses: Thai curries, soups, pilafs and gratins, baked goods.

Other varieties: Hokkaido, Japanese Uchiki.

Spaghetti

These football-sized, bright yellow squash are very different from other varieties in this family. Spaghetti squash has a pale golden interior, and is stringy and dense—in a good way! After sliced in half and baked, use a fork to pry up the strands of flesh and you will see it resembles and has the texture of perfectly cooked spaghetti noodles. These squash are not particularly sweet but have a mild flavor that takes to a wide variety of preparations.

Selection: choose a bright yellow squash that is free of blemishes and soft spots.

Best uses: baked and separated, then mixed with pesto, tomato sauce, or your favorite pasta topping.

Sweet Dumpling

These small, four- to-six-inch round squash are cream-colored with green mottled streaks and deep ribs similar to Acorn. Pale gold on the inside, with a dry, starchy flesh similar to a potato, these squash are renowned for their rich, honey-sweet flavor.

Selection: pick a smooth, blemish-free squash that is heavy for its size and is evenly colored. Avoid a squash that has a pale green tint as it is underripe.

Best uses: baking with butter and cinnamon.

Miscellaneous Varieties

At some food co-ops, farmer’s markets, and apple orchards in the fall you may encounter unusual heirloom varieties of squash that are worth trying. If you like butternut, look for Galeux D’eysines, a rich, sweet and velvety French heirloom that is large, pale pink, and covered in brown fibrous warts. You might also like to try Long Island Cheese squash, a flat, round ribbed, beige squash that resembles a large wheel of artisan cheese.

If you prefer the firmer, milder Acorn, you might like to try long Banana or Pink Banana squash. If you like a moist,dense textured squash (yam-like), try a Queensland Blue or Jarrahdale pumpkin. These huge varieties are from Australia and New Zealand, respectively, and have stunning brittle blue-green rinds and deep orange flesh. Both are good for mashing and roasting.

Seward-made Sausages

Here at Seward Co-op, we take pride in working directly with local farmers, processing whole carcass animals in-house, and having a large variety of fresh, Seward-made sausages. We work directly with many small local farms that we have had the opportunity to visit and see firsthand how the animals are raised and handled. Check out our new seasonal sausages (left)!

Have you tried the Franklin Frank? Summer is the perfect time, if you haven’t already. Our sausage makers have handcrafted the perfect old-fashioned hot dog! It’s made in our own production facility on Franklin Ave. The ingredients are 100% locally sourced and the herbs and spices are all organic—no filler. Stop by our full-service meat counter and pick up some dogs to grill at the park! Or have us grill it to perfection for you at the café, topped with house-made pickles, onions and mustard. Get creative and check out our amazing selection of locally made condiments. Kimchi, sauerkraut, pickles, mustard, hot sauce—we have it all!

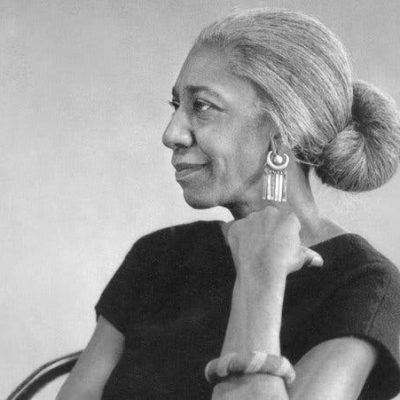

Edna Lewis The Grand Dame of Farm-To-Table

The Farm-to-Table movement promotes the importance of producing food locally and delivering that food to local consumers. Linked to the local food movement, Farm-toTable is mainly promoted by the restaurant communities. Among the well-known patron saints of Farm-to-Table are Michael Pollan, Dan Barber and Alice Waters. There is one name that is just as important to the movement, albeit not as well known to those outside of the culinary world — Edna Lewis.

For centuries, blacks have cooked in Southern kitchens, on plantations, in mansions, in boarding houses and hotels, and on riverboats. This was affirming work that encouraged black women to embrace the myriad ways our foremothers used food for economic freedom and independence, community building, cultural work and to develop personal identity.

Long before it became a movement, Farm-to-Table was a way of life for many Americans in the South. This was true for Edna Lewis. Miss Lewis, as she was called, grew up in Freetown, Va. The name was adopted because the first residents had all been freed from chattel slavery and wanted to be known as a town of free people.

Miss Lewis had no formal culinary training. Her classical presentation of Southern food made you, as Chef Joe Randall says, want “to put the South in your mouth.” She went on to become a celebrated black chef in New York in the late 1940s and 1950s, when there were few, if any, other black or female chefs working in the city. Edna learned to cook alongside her family. They cooked food that was always fresh from the gardens, fields, woodlands, rivers and lakes nearby. The food was simply prepared but made with great care and devotion. Edna wove these lessons into the foundation of her cooking style.

“We lived by the seasons,” she wrote, in The Taste of Country Cooking. Two of the chapter headings read, “An Early Summer Dinner of Veal Scallions and the First Berries” and “Emancipation Day Dinner” in the fall, which she described in a 1993 NPR interview.

She explained, “the food that you would carry would be the food of fall, which included game, and a lot of people carry roast chicken, which was a chicken that had become of age and you no longer could fry. And of course, pork and fall greens like turnip greens or mustard greens. And sweet potatoes and pickles and preserves and yeast bread and some dessert like deep-dish apple pie or damson plum pie.”

Sometimes fried chicken is just about the chicken. In the South, where paradoxes live next door to each other and race, class, and gender clash with particular complexity, it can be about much more. Food can be about families broken and mended, unlikely friendships, and redemption. Examining the complex relationship between racist and realistic characterizations of our food traditions, we must acknowledge the destructive legacy associated with negative images of African American food choices. It is through remembering Miss Lewis’s contribution to the contemporary food movement that we are able to acknowledge and honor that legacy on our plates.

Spicy Collards in Tomato-Onion Sauce

“As a child in Virginia, Miss Lewis says, she didn’t even know there was such a thing as collard greens. And though we knew them in Alabama, we thought of them as crude and didn’t eat them. Now I love them, however, whether simply cooked in pork stock or finished, as here, in a spicy tomato sauce. (Miss Lewis will eat collards when I cook them but seems to have no interest in preparing them herself.) Other greens are also delicious served in this sauce — especially escarole — but most will need far less cooking time than collards.” — Jemimah Code

Ingredients

1 ½ pounds collard greens

6 cups vegetable or beef stock

3 Tbsp. olive oil

1 large onion, chopped (about 1 ¼ cups)

1 Tbsp. minced garlic

½ tsp. crushed red-pepper flakes (more or less, according to taste)

½ tsp. each salt and freshly ground black pepper

38 oz. canned whole, peeled tomatoes, drained

Method

Wash and drain the collards. Remove the stems and discard. Cut the collard leaves crosswise into 1-inch strips. Bring the stock to a rolling boil in a large Dutch oven, drop in the collard greens, and cook, uncovered, for 30–40 minutes, until tender. Drain the greens, and reserve the cooking liquid. Heat the olive oil in a large skillet or Dutch oven. Add the onion and cook, stirring often, over moderate heat for 10 minutes, until the pieces are translucent and tender. Add the garlic and crushed red pepper, ½ teaspoon of salt, and ½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper. Stir well to distribute the seasonings, and cook for an additional 5 minutes. Add the drained tomatoes and 1 ½ cups of the liquid reserved from cooking the greens. Simmer gently for 15 minutes. Taste for seasoning, and adjust as needed. Add the drained collard greens, and simmer for an additional 10 minutes. Taste for seasoning again, and serve hot. Serves 6.

Adapted from The Jemimah Code

A Cooperative Legacy

Until recently, if you asked where cooperatives originated, many people would cite the Rochdale Pioneers. These were the 28 textile mill workers from the town of Rochdale, England, who formed the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society in 1844 in response to poor working conditions, low wages, adulterated food and exploitation. They created the first sustainable cooperative business and are credited with articulating the guiding principles that became what we know today as the International Cooperative Principles.

The story of cooperation, and furthermore cooperative economics, is not exclusive to Europeans; it has been adopted by countless cultures around the globe. This is particularly true in African American history. Cooperative Hall of Famer Jessica Gordon Nembhard opens the door to critical aspects of Black cooperative history in her book “Collective Courage.” Nembhard continues the research of W.E.B. Du Bois from the early 20th century to catalogue the extensive efforts of African American cooperatives. She places co-ops solidly as precursors to and tools used in the Civil Rights Movement. She clearly demonstrates that the co-op narrative belongs to everyone.

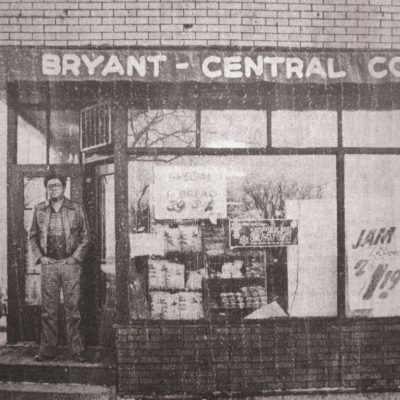

Tom Pierson, a local research assistant to Dr. Nembhard, shared in a recent interview with the filmmakers of Radical Roots that the Twin Cities was home to multiple “first wave” cooperative grocery stores — five of which were predominantly African American based. Many of these started in the early 1940s, more than three decades prior to the majority of “new wave” food co-ops that operate today. Pierson discovered many of these co-ops in his research of the Franklin Cooperative Creamery (FCC) for Seward Co-op. FCC built the Creamery building and supported these first wave co-ops. Of the five African American co-ops that existed, a few shared neighborhoods with the food co-ops today: the Sumner Cooperative operated in the Harrison neighborhood of North Minneapolis, near the site of the soon-to-open Wirth Co-op; the Co-ops, Inc. of Minneapolis that served the Bryant and Central neighborhoods with a store at 41st Street and Chicago Avenue, was near Seward’s current Friendship store; and the Credjafawn Co-op Store, a project of the Credjafawn Social Club, was located in St Paul’s Rondo neighborhood near Mississippi Market’s present-day Selby-Dale store.

African American co-ops also formed simultaneously with Seward Co-op and other new wave co-ops. As in the ’40s, these were located in North Minneapolis, Rondo and the Bryant-Central neighborhoods. The Bryant-Central Co-op opened in the mid-1970s and was started by Moe Burton, uncle of Gary Cunningham, the executive director of Metropolitan Economic Development Association and spouse of Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges.

Pierson notes that co-ops in this era were typically run by unpaid volunteers. However, the Bryant-Central Co-op was a pioneer when it came to paying staff and thinking big. They envisioned a store more than twice the size of most large co-ops today. Unable to raise the capital to build to scale, Bryant-Central Co-op closed in 1978. Burton and others in the community attempted to start a new co-op in the mid-1990s, but due to Burton’s untimely death, as well as a lack of resources, the store never materialized.

At Seward Co-op we are proud to honor and build on the legacies of past cooperators. People like W.E.B. Du Bois, Mo Burton and groups like the Credjafawn Sociai Club, not to mention, the countless unnamed individuals that did the physical work of starting first wave co-ops are critical in our understanding of the stories of those who came before us. Communities, like our own, have used cooperatives in order to end oppression and eradicate injustices, particularly in food justice.

The Legacy of African Americans in Co-ops

February is recognized as Black History Month in the United States. Traditionally, its focus has been to celebrate the contributions of African Americans in the U.S.

Carter G. Woodson pioneered the celebration that started as out as a week in February in 1926, to its current month-long celebration. As we approach the opening of the Friendship store in Bryant neighborhood, it is important that we honor the legacy of African Americans in the co-op community.

The book Collective Courage by Jessica Gordon Nembhard documents the importance of cooperative economics in the African American community. In that book, Dr. Nembhard covers decades of experiences that African Americans have had with cooperative economics.

Customers at Minnesota’s Credjafawn Co-op in the predominantly African-American Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul, circa 1950.

Dr. Nembhard’s book is a continuation of the 1907 survey of African American cooperative efforts written by W.E.B. Du Bois. Du Bois discussed how African Americans used racial solidarity and economic cooperation in the face of discrimination and marginalization.

According to Dr. Nembhard, Du Bois differentiated cooperative economics from Black capitalism or buying Black. Du Bois focused on a “Black group economy” to insulate Blacks from continued segregation and marginalization.

To achieve that goal, Du Bois organized the Negro Cooperative Guild in 1918 with the idea of advancing cooperation among Black people. In attendance at the two-day conference were 12 men from seven states.

Du Bois is most widely known for his statement regarding race relations in the U.S. In his book, The Souls of Black Folk, he famously noted that “the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line.”

Du Bois is noted for accurately describing the problems of race in America. Yet, his work to solve the problem of the color line is often ignored. Du Bois promoted economic cooperation as the solution to the issues of the “color line.”

Du Bois said that “we unwittingly stand at the crossroads—should we go the way of capitalism and try to become individually rich as capitalists, or should we go the way of cooperatives and economic cooperation where we and our whole community could be rich together?”

In this instance, Du Bois believed that economic cooperation could provide more than providers of goods or services, but also a philosophy or blueprint by which communities could be built or rebuilt.

The guild’s mission was to encourage the study of consumer cooperatives and their methods, support the development of cooperative stores, and form a technical assistance committee.

As a result of the meeting of the guild, in 1919, the Memphis group incorporated as the Citizens’ Co-operative Stores to operate cooperative meat markets. The venture was very popular. The cooperative sold double the amount of the original shares they offered, and members could buy shares in installments.

Within a few months, five stores were in operation in Memphis, serving about 75,000 people. The members of the local guilds associated with each store met monthly to study cooperatives and discuss issues. The cooperative planned to own its own buildings and a cooperative warehouse.

The use of cooperative economics to address racial discrimination in the market place and provide a pathway to rebuild communities is an important lesson that has relevance today.

Since the 1800s, Minnesota food co-operatives have been at the center of issues that juxtapose the pursuit of justice issues against fair market opportunity. This started with the Finnish who arrived in Northern Minnesota, Scandinavian farmers who were taking bottom-barrel prices from railroad barons, extended into the 1950s when Black Minnesotans organized the Credjafawn Co-op to benefit their community in St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood. The co-ops were at the center of these issues in the 1970s, too, wherein the “Co-op Wars” erupted over social justice issues versus profitability.

We know that these are false dichotomies. A single choice among fairness, equity, or justice is not an option. Justice in the marketplace is not an option. Economic exploitation is not a part of the model of sustainability, and neither is economic isolation. The opportunity to share the co-operative model is at hand.

During the Co-op Wars of the ’70s, the clash between the Maoist “Co-op Organization” and the Bryant/Central Food Co-op was not just about food. The clash was about the false dichotomies: Serving poor people OR serving great food. Dismantling the notion that “cheap” food is sustainable is hard.

However, we now know that cheap food is built on cheap labor. When people are not paid fairly, we perpetuate the same system of inequality that we are trying to end. Today’s food co-ops must accomplish both: Make a commitment to end poverty by supporting economic models that are fair, just, and healthy and deliver healthful food to its owners.

The Seward Co-op’s Friendship store in a Bryant neighborhood will be an opportunity to become a part of the fabric of the community that honors this legacy by bridging the gap between the promise of cooperatives of the past and an economically just future.

Would you like to discuss these ideas further? Join LaDonna for the Seward Co-op Book Club this month —Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice