The farm-to-table movement promotes the importance of producing food locally and delivering that food to local consumers. Linked to the local food movement, farm-to-table is mainly promoted by restaurant communities. Among the well-known patron saints of farm-to-table are Michael Pollan, Dan Barber and Alice Waters. There is one name that is just as important to the movement, albeit not as well known to those outside of the culinary world — Edna Lewis.

For centuries, blacks have cooked in Southern kitchens, on plantations, in mansions, in boarding houses and hotels, and on riverboats. This was affirming work that encouraged black women to embrace the myriad ways our foremothers used food for economic freedom and independence, community building, cultural work and to develop personal identity.

Long before it became a movement, farm-to-table was a way of life for many Americans in the South. This was true for Edna Lewis. Miss Lewis, as she was called, grew up in Freetown, Va. The name was adopted because the first residents had all been freed from chattel slavery and wanted to be known as a town of free people.

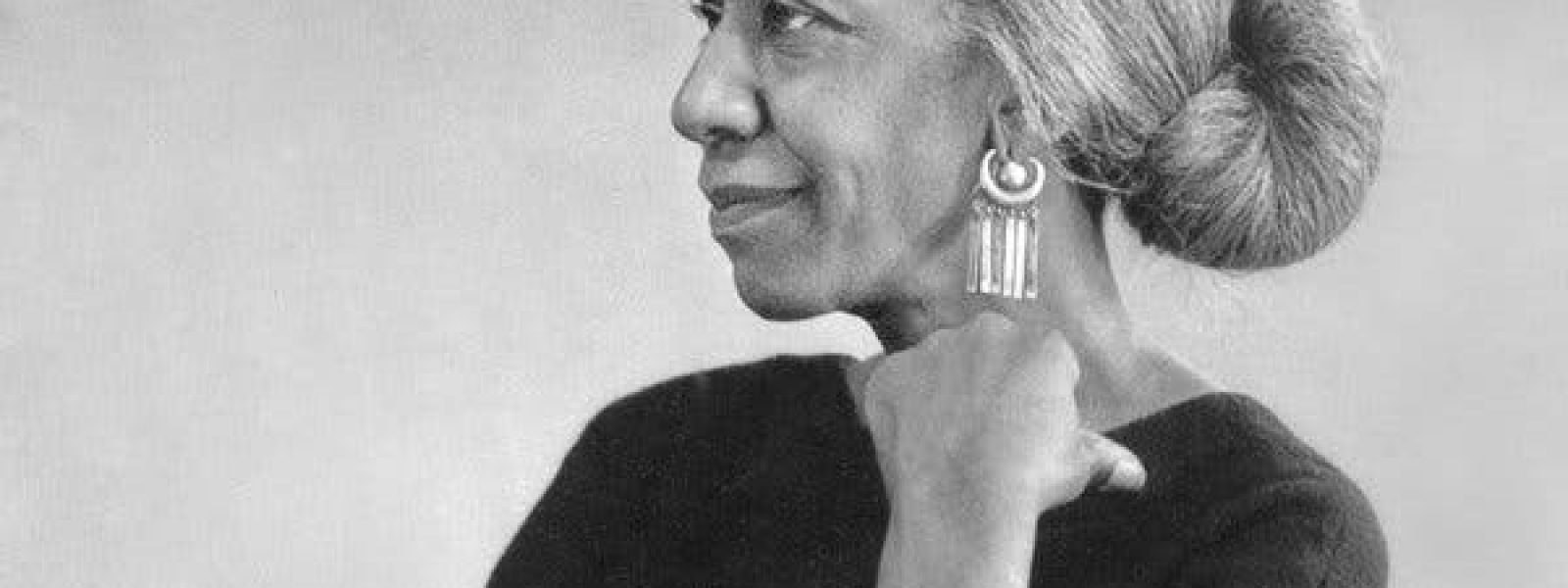

Miss Lewis had no formal culinary training. Her classical presentation of Southern food made you, as Chef Joe Randall says, want “to put the South in your mouth.” She went on to become a celebrated black chef in New York in the late 1940s and 1950s, when there were few, if any, other black or female chefs working in the city. Edna learned to cook alongside her family. They cooked food that was always fresh from the gardens, fields, woodlands, rivers and lakes nearby. The food was simply prepared but made with great care and devotion. Edna wove these lessons into the foundation of her cooking style.

“We lived by the seasons,” she wrote, in The Taste of Country Cooking. Two of the chapter headings read, “An Early Summer Dinner of Veal Scallions and the First Berries” and “Emancipation Day Dinner” in the fall, which she described in a 1993 NPR interview.

She explained, “the food that you would carry would be the food of fall, which included game, and a lot of people carry roast chicken, which was a chicken that had become of age and you no longer could fry. And of course, pork and fall greens like turnip greens or mustard greens. And sweet potatoes and pickles and preserves and yeast bread and some dessert like deep-dish apple pie or damson plum pie.”

Sometimes fried chicken is just about the chicken. In the South, where paradoxes live next door to each other and race, class, and gender clash with particular complexity, it can be about much more. Food can be about families broken and mended, unlikely friendships, and redemption. Examining the complex relationship between racist and realistic characterizations of our food traditions, we must acknowledge the destructive legacy associated with negative images of African American food choices. It is through remembering Miss Lewis’s contribution to the contemporary food movement that we are able to acknowledge and honor that legacy on our plates.