Until recently, if you asked where cooperatives originated, many people would cite the Rochdale Pioneers. These were the 28 textile mill workers from the town of Rochdale, England, who formed the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society in 1844 in response to poor working conditions, low wages, adulterated food and exploitation. They created the first sustainable cooperative business and are credited with articulating the guiding principles that became what we know today as the International Cooperative Principles.

The story of cooperation, and furthermore cooperative economics, is not exclusive to Europeans; it has been adopted by countless cultures around the globe. This is particularly true in African American history. Cooperative Hall of Famer Jessica Gordon Nembhard opens the door to critical aspects of Black cooperative history in her book “Collective Courage.” Nembhard continues the research of W.E.B. Du Bois from the early 20th century to catalogue the extensive efforts of African American cooperatives. She places co-ops solidly as precursors to and tools used in the Civil Rights Movement. She clearly demonstrates that the co-op narrative belongs to everyone.

Tom Pierson, a local research assistant to Dr. Nembhard, shared in a recent interview with the filmmakers of Radical Roots that the Twin Cities was home to multiple “first wave” cooperative grocery stores — five of which were predominantly African American based. Many of these started in the early 1940s, more than three decades prior to the majority of “new wave” food co-ops that operate today. Pierson discovered many of these co-ops in his research of the Franklin Cooperative Creamery (FCC) for Seward Co-op. FCC built the Creamery building and supported these first wave co-ops. Of the five African American co-ops that existed, a few shared neighborhoods with the food co-ops today: the Sumner Cooperative operated in the Harrison neighborhood of North Minneapolis, near the site of the soon-to-open Wirth Co-op; the Co-ops, Inc. of Minneapolis that served the Bryant and Central neighborhoods with a store at 41st Street and Chicago Avenue, was near Seward’s current Friendship store; and the Credjafawn Co-op Store, a project of the Credjafawn Social Club, was located in St Paul’s Rondo neighborhood near Mississippi Market’s present-day Selby-Dale store.

African American co-ops also formed simultaneously with Seward Co-op and other new wave co-ops. As in the ’40s, these were located in North Minneapolis, Rondo and the Bryant-Central neighborhoods. The Bryant-Central Co-op opened in the mid-1970s and was started by Moe Burton, uncle of Gary Cunningham, the executive director of Metropolitan Economic Development Association and spouse of Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges.

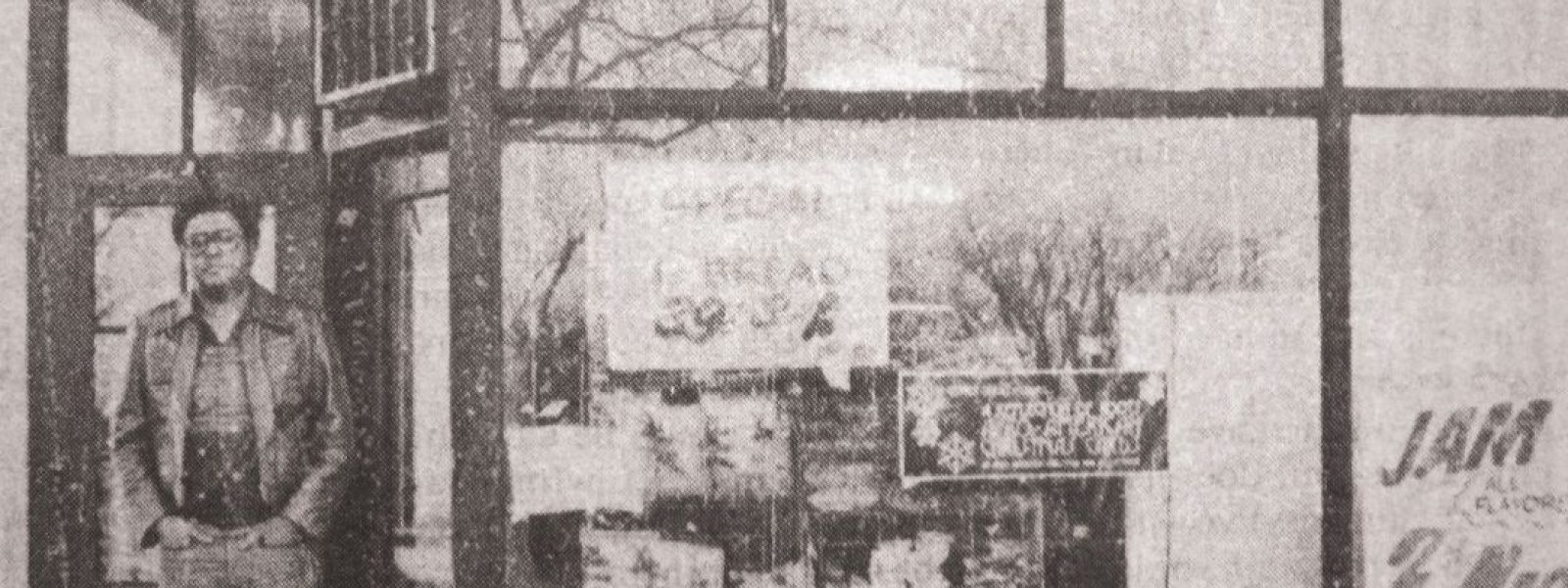

Pierson notes that co-ops in this era were typically run by unpaid volunteers. However, the Bryant-Central Co-op was a pioneer when it came to paying staff and thinking big. They envisioned a store more than twice the size of most large co-ops today. Unable to raise the capital to build to scale, Bryant-Central Co-op closed in 1978. Burton and others in the community attempted to start a new co-op in the mid-1990s, but due to Burton’s untimely death, as well as a lack of resources, the store never materialized.

At Seward Co-op we are proud to honor and build on the legacies of past cooperators. People like W.E.B. Du Bois, Mo Burton and groups like the Credjafawn Sociai Club, not to mention, the countless unnamed individuals that did the physical work of starting first wave co-ops are critical in our understanding of the stories of those who came before us. Communities, like our own, have used cooperatives in order to end oppression and eradicate injustices, particularly in food justice.